After our exhilarating but exhausting journey from Manali, the four of us paused for a couple of days in Leh before continuing our adventures. This is therefore probably a good opportunity to pause as well in the narrative, and offer a short introduction to Ladakh.

Upon arriving from Himachal Pradesh, one's strongest impression of Ladakh is how much it contrasts with "mainland" India, in almost every possible way. Indeed, it was only through the vagaries of nineteenth-century imperial history that this kingdom, which had been independent but within Tibet's sphere of influence for almost a millenium, ended up as part of India--basically, it happened to be grabbed by Kashmir just before Kashmir was grabbed by the British. It thus now finds itself part of the war-torn state of Jammu & Kashmir. The Ladakhis, however, make no common cause with Kashmiri separatists; instead many are campaigning to become an independent state (or union territory) within India. Due to the proximity to Kashmir, as well as the ongoing border dispute with China, there is a massive military presence in the region, with huge Indian Army bases on both sides of Leh.

To understand the human geography of Ladakh, there are basically two primary facts you need to know. The first is the obvious one of the high altitude and mountainous terrain. The valleys are typically between 3,000 and 4,000 meters, the peaks between 5,000 and 7,000. Connecting the valleys are the "many passes" that give Ladakh its name. The other primary fact is that Ladakh is one of the few regions of India that is not hit by the monsoon, which is stopped cold by the Himalaya on its way north. The almost total lack of rainfall would make Ladakh uninhabitable, if it weren't for the snow that falls on the high peaks and turns (sometimes after being locked up in a glacier for many years) into plentiful streams that nourish the valleys below. Thus the crops--principally wheat, barley, potatoes, and apricots--are watered almost entirely by irrigation. One of the most charming aspects of Ladakh is the ubiquitous gurgling water channels--anything from a simple ditch to a 5 meter wide canal--that run alongside practically every path, be it a street in Leh, a highway between towns, or trail along a steep mountain slope. The flat valley bottoms are for most part very narrow, and their green fertility makes a vivid contrast to the steep, barren mountain slopes that pen them in.

The villages are located in the valley bottoms near the fields. Their white-washed houses are typically two storeyed, with wide, wood-panelled windows, decorative woodwork over both windows and doors, and flat roofs covered with grass drying for the winter. The gompas (monasteries) are often close to a village but always a bit isolated, on a small peak or steep mountainside nearby. The slopes sometimes support just enough grass to graze a very dispersed herd. Although we were expecting to see many yaks, the most common large livestock turned out to be the dzo, a cross between a cow and a yak. Sheep and goats are also common.

One valley that is definitely not narrow is that of the Indus River, which meanders through the broad plain between the Zanskar Range (to the south) and the Ladakh Range (to the north), at around 3,500 m, on its way from Tibet to Kashmir. The Indus is the backbone of Ladakh, and most of the population (including the capital, Leh) lives in its valley.

In general, Ladakhis have a remarkably calm and peaceful demeanor; they tend to be quiet but are always friendly and polite. Walking down the street, one is constantly greeted with a friendly "jullay" (meaning hello, goodbye, thank you, and probably several other things) by young and old alike. As you will see in the pictures below, the Ladakhi people have a very curious appearance that defeats any attempt to put them into the usual racial categories. Their skin is often very pale, with rosy cheeks, and their features vary from Chinese to Turkish. The language, Ladakhi, is a variant of Tibetan. Many also speak Hindi, and a smaller number a bit of English (however, the girls we met at Wanlah were learning English, not Hindi, in school). Ladakh hosts a large number of Tibetan refugees, and one sees many Indians from other parts of the country: Kashmiri salesmen, Bihari road-workers, and of course many soldiers from all over the country.

The local dishes of Ladakh are quite varied: vegetable momos (dumplings), meat momos, yak cheese momos, momos in broth, on and on. If it wasn't momos then it was some kind of noodles--thukpa, skyu, chutagi--in broth, generally with vegetables, yak cheese, or meat. While we were there a white-purple radish-like root called shalgam was in season; we saw piles of it everwhere and ended up eating all parts of it in different forms in various meals (momos, thukpas, salads, chowmein, saag paneer). Then of course there is the famous salty yak butter tea, which is quite good if you follow the advice of the our guidebook and think of it as soup. Inevitably, there is also a local alcohol, in this case a home-brewed wheat beer called chhang, that was fizzy and sour but had a good kick to it. Both the tea and the chhang were often supplemented by mixing in tsampa, roasted barley flour.

Ladakhis follow the Tibetan, Mahayana form of Buddhism. All around one sees chortens, prayer wheels and prayer flags. The chortens seen around town usually contain ashes or sacred objects of important Rimpoches (lamas). The ones found in gompas are often silver in colour and are embedded with semiprecious gems. The prayer wheels contain reams of the prayer "Om Mani Padme Hum" written over a million times. The prayer wheels as well as the chortens should always be circled clockwise.

Chortens in a field on the outskirts of Leh

Minette increasing her karma by one million "Om Mani Padme Hum"s

Matt is pretty sure that this one really is a yak

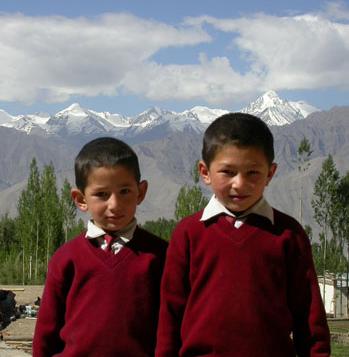

After our first night in Leh, staying at the first hotel we stopped in, Jayashree found us a beautiful (and cheap) little guest house aptly called Skit Tsal (Garden of Peace) in the suburb of Karzoo, where the streets are narrow and lined with stone walls and small canals with rushing water. The houses in Karzoo are surrounded by gardens, and indeed the one around our own guest house supplied the fresh vegetables that went into our dinners (for example, shalgam momos) when we were too tired or lazy to walk into town. Our hosts were gracious and extremely friendly, and had two adorable and very well brought up sons.

On our first real day in Leh, Jayashree continued to recuperate back in the guest house, while the rest of us set out to explore the town. The altitude (3,500 m) didn't make us sick, but it did have the effect of turning walking, even very slowly, into a major aerobic activity; feeling slightly silly, we had to stop and catch our breath every few steps. The center of town essentially caters to tourists, but in contrast to Manali, walking down the streets of Leh is a pleasant experience. Down Main Market and Fort Road one sees plenty of Kashmiri stores selling Pashmina shawls (fake and real), woollen clothes, carpets, etc., as well as shops selling Tibetan handicrafts, trinkets made of semi-precious stones, and so on. Although Leh isn't very good for shopping, it is fun to potter around the shops amusedly listening to shopkeepers try to convince you of the authenticity of their wares. The old town of Leh, just above the Jamia Masjid, is in contrast to the newer parts, with small, narrow, winding streets and two- and three-storeyed building built close to one another. We eventually found our way out of the main part of town and to the Sankar Gompa, the head gompa of the Leh area. From there we very gradually climbed the road (most of it, anyway--we caught a lift for the last kilometer) up to the Shanti Stupa, a modern shrine built by the Japanese whose main claim to fame is the magnificent view it commands over Leh and the Indus Valley. On the way back to our guest house, we noticed a crowd of people gathered at the entrance to a hotel waiting, we overheard, for the movie actor Om Puri (My Father the Fanatic, East is East, The Mystic Masseur, City of Joy, The Jewel in the Crown) to come out. We passed the crowd, and almost walked straight into Om Puri himself, who had snuck out of a side door!

The cardinal kings of North and South guarding the gates of heaven,

on the wall of the foyer of the Sankar Gompa's Du-Khang (Assembly

Hall)

A magpie, very common in Ladakh

Matt, David, and Minette, at the Shanti Stupa

The Leh Gompa as seen from the Shanti Stupa

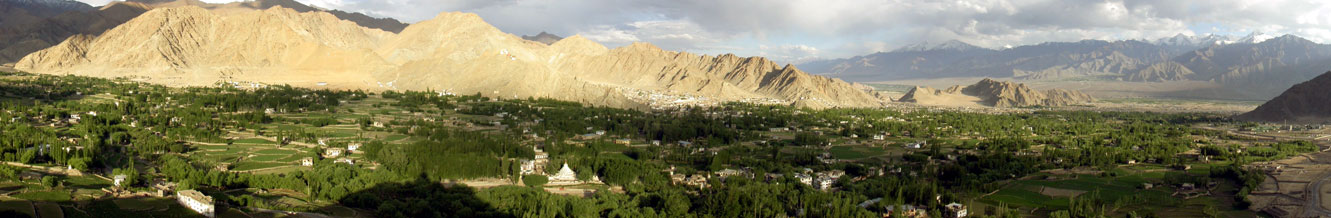

Changspa, Karzoo, Leh, and the Indus Valley from the Shanti Stupa. The

suburbs of Changspa and Karzoo, in

the foreground, are green and spread out, while the center of Leh,

nested between two ridges and overlooked by the

Leh Gompa, is dry and compact. The Indus River is visible as a green

line on the right, and behind it are the snow-capped peaks of the Stok

Range. (Scroll right to see the whole thing.)

The next day David and Matt wandered around town a bit more, while Jayashree and Minette paid a visit to Dr. Narboo in Old Leh. There was a long queue to see him and one needed to collect a token number from the chemist below to get in line. He was a shortish, round, kindly old man with an air of seriousness. He pronounced both of us ill with Acute Altitude Sickness, and predicted dire consequences if we didn't heed his advice. He shook his head gravely when we told him we had driven up from Manali--the ups and downs are too quick and and too many. The next time you come to Ladakh, he warned, be sure to fly on the way in and then enjoy the road on the way back. Jayashree was impressed by his prescription of live lactobacilli with antibiotics.

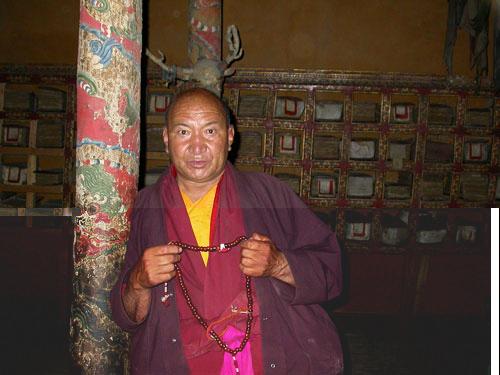

In the afternoon David braved the rigors of a not completely flat road to visit the Leh palace; here's his report. Right behind the touristy center of the Main Street Bazaar, and in strong contrast to the leafy spacious farmyards and guesthouses of Karzoo, the old town of Leh consists of a maze of small streets full of cloth-dyeing, Ladakhi-bread-making, little kids playing, and countless dogs. There didn't seem to be an official way to get up to the Leh palace, but at every turn friendly Leh-ites provided directions which led from one backyard to another, winding upward (against my oxygen-dependent inclinations) to the palace gates. The sun was setting over the old town, and the palace area had emptied of tourists, but a monk beckoned me over to one of the side gates and let me in (for the standard fee). He walked me around the various parts of the palace, interrupting his constant Om-mani-padme-hum chanting periodically to exchange shouted comments with monks on other tiers of the palace compound. The palace commands an excellent view of the town, and some interesting wall paintings, but is in a shocking state of disrepair; given the lack of lighting or an organized path, it made for an exciting obstacle course in the dark, with occasional large holes in the floor. After emerging from the palace, I was passed around from one monk to another as I passed between the four or five different temples/dormitories on the gompa complex, each covered with sculptures and detailed wall paintings, when there was enough light to see them. They emerged in vibrant colors when the camera flashed (mea culpa). The monks were quite intrigued by the camera and expressed their great approval on seeing the paintings and themselves appear on the little screen..

Monk at the Leh gompa

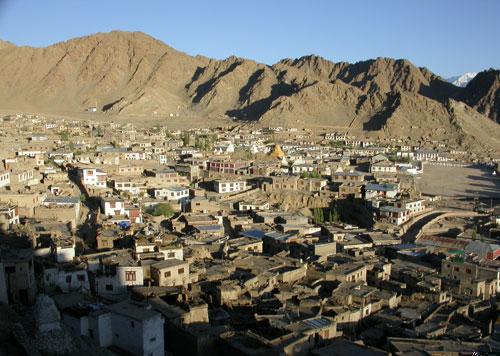

View of the old town of Leh from the gompa

Through Ladakh's clear rarified air, the night skies were utterly breathtaking. The rising Mars in the east looked so unbelievable we mistook it for a red lamp on the hill beyond (turns out we were heading towards the closest approach to Mars in perhaps 60,000 years - on August 27, 2003, Mars will be the brightest object in the sky).

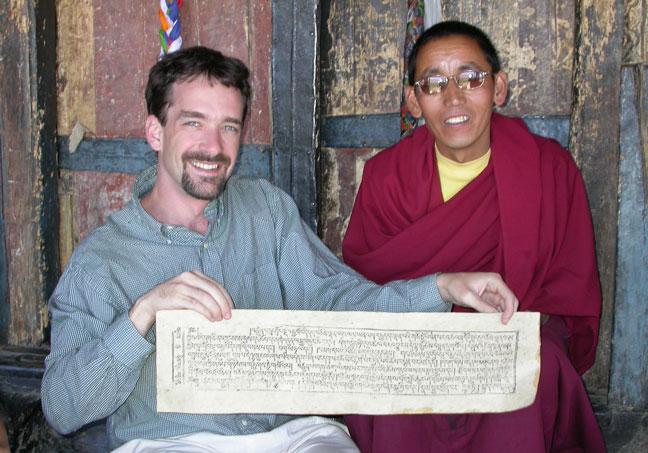

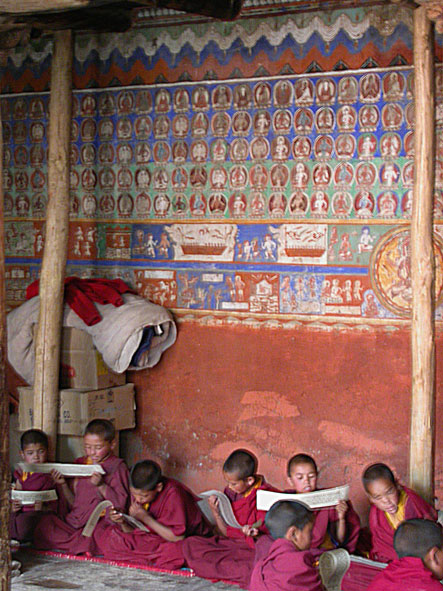

The next day, on doctor's orders, Jayashree and Minette stayed back to recuperate, while David and Matt rented a car and set off on a tour of the gompas to the south of Leh. We set out very early to see the morning prayer ceremony at Thikse. We drank yak butter tea and observed the very individualistic recitiation of the monks (of ages ranging 5 to 50). After this we studiously embarked on the project of learning some of the Mahayana Buddhist iconography, including the main Boddhisattvas, countless guardian deities (mahakalas), the wheel of life and mandala, the eight auspicious symbols, the four friends etc. We saw Thikse's 16-foot Maitreya Buddha sculpture, and also managed to stumble upon the roof of the gompa, from which we got our best view of the Indus valley. A very friendly monk let us see some of the sacred texts stored in the gompa's manuscript library, and explained to us why Bush is a good president...

The gompa at Thikse

The Indus valley, from the roof of Thikse gompa (scroll right to see the whole thing)

A wallpainting at Thikse

Matt and his new friend studying at Thikse

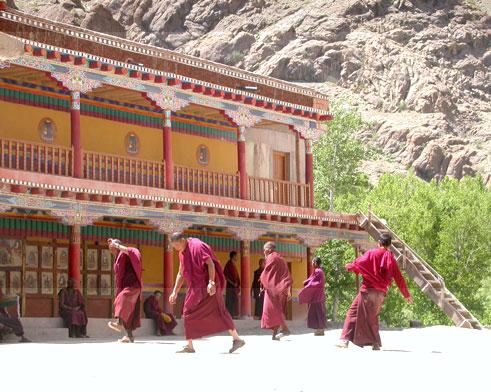

From Thikse we went to Hemis, the largest and richest of the gompas, where we chanced upon a group of monks practicing their dancing in preparation for the huge Hemis Festival a few weeks later. As with all other Ladakhi gompas we saw, Hemis was located spectacularly, hidden in a steep offshoot of the main Indus valley (leading to the question, if it were actually possible to build a nonspectacularly situated gompa in Ladakh). Hemis boasts several lavishly decorated assembly halls, and an enormous 1999 sculpture of a friendly-looking Padmasambhava, the patron saint of the Hemis festival, who brought Buddhism to Tibet.

Practicing for the Hemis festival

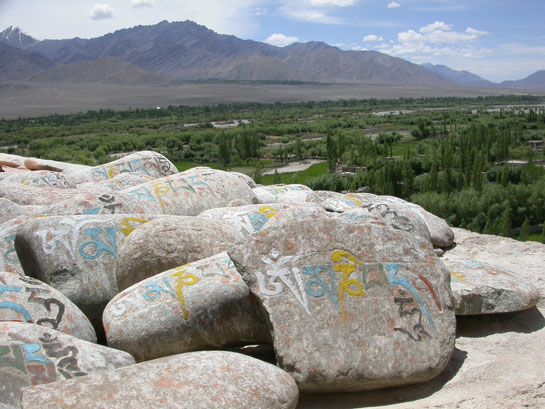

Next we went to Shey, the oldest of the gompas and the one which held the greatest surprises. The 16th wallpaintings in Shey were spectacular, and a great test for our iconographic skills honed on the newer paintings in Thikse and Hemis. Shey also boasts a beautiful 16th century two-story-tall sculpture of the Buddha. We also finally noticed the omnipresent Mani Walls -- short stone walls covered with rocks, on which is carved the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum (also written innumerable times inside the prayer wheels). Finally and most excitingly, we almost accidentally ran into a great boulder, on which were faintly carved 8th century images of the five Tiyani Buddhas. (Thanks to the wonders of photo processing, you too can enjoy these images now.)

A mani wall at Shey

The great Buddha of Shey

The goddess Tara, as depicted at Shey

The five Tiyani Buddhas outside Shey

The tour concluded with a visit to the royal palace at Stok, which to this day houses the heirs to the throne of Ladakh (Namgyal family) and a slightly surreal musesum, showing the riches of the kings and queens, portraits of famous visitors such as Nehru and Indira Gandhi, and an honorary membership for the queen mother in a south suburban Chicago police force. By now we were also no longer oblivious of the mani walls radiating in all directions, which together with countless white chortens decorate the entire Ladakhi countryside. We were also invited to perform Sindhu Darshan, a tribute to the holy Hindu river Indus, instituted very recently by India's ruling BJP for dubious political agenda in this predominantly Buddhist region.

The boys at our guest house, with the Stok Range behind them

The next day (thanks to the help of the doctor) everyone was feeling better, and we set out in full force to see some of the gompas to the north of Leh. The streets of Leh were festooned with banners and lined with schoolchildren holding little flags and roses. All of this was not for our benefit of course, but for that of President Abdul Kalam, who was dropping by Leh for a visit that day. And it was accompanied by a show of military force, with soldiers behind every tree and (once we were out of town on the road to Kargil) on every hilltop along the road.

Art-wise, our warmup that day (after a very questionable breakfast at Nimmu, the confluence of the Zanskar and Indus -- cf. Day 5 of our trek) was the (yes, spectacularly situated) gompa at Likir, where we discovered the joys of having a professional guide, as Phuntsog explained to us the intricacies of the wheel of life and other icons we were seeing. We also saw an excellent collection of thangkas, the silks painted with stone colors and gorgeous images of the life of Buddha, Boddhisattvas and saints, and cowered under a gigantic five-year-old statue of the Maitreya Buddha, the future Buddha, enthroned in Heaven while awaiting his descent to earth. Apparently tourism has been quite good for Ladakh's monasteries!

Likir gompa

The wheel of life

A view down from Likir

We then reached the star attraction of the Ladkahi gompa tour, the monastery of Alchi (now defunct), located on the banks of the Indus. This 11th century masterpiece is fairly unremarkable on the outside, but the insides of the large collection of temples there are covered from floor to ceiling with superlative paintings. Upon arrival we entered the main hall, where we sat silently for an hour, observing monks from Likir chanting, playing drums, blowing horns. Three little monks alternated trying to blow the conch, and giggled uncontrollably in between. The monks continue to do this until they have performed all of the thousands of hand positions (mudras) indicated in their texts and on the walls of Alchi, which as we realized takes far longer than our car was willing to wait. As our eyes adjusted to the strange surroundings of the dimly lit room, slowly the gorgeous mandalas covering all of the walls came into focus. Luckily (?) we didn't realize photography was forbidden until we had filmed a short film of the event, which one day will make it to this webpage! When the monks took a much-needed break, we got to inspect the room in detail, including the many Persian-influenced miniatures and gorgeous statues of Vairocana, to whom the temple was dedicated. Besides this main hall, Alchi boasts a stunning three-tiered temple, also covered floor to ceiling with detailed paintings in an assortment of styles and three gigantic painted statues of Avalokitshvara (Boddhisattva of Compassion), Manjusri (Boddhisattva of Wisdom) and Maitreya (the future Buddha)--and sadly also with no photography (even with David's no-flash-needed digital camera)--sorry, go to your local library and check out a book on Alchi!

Rinchen Zangpo (the Translator) at Alchi

Young monks from Likir at Alchi

One of Alchi's mandalas

Statues in Alchi

After parting from Jayashree, who continued on to SECMOL, and exploring the assorted temples, we (now Matt, Minette, and David) scrambled down to the banks of the Indus, which had just completed an exciting turn around the bend. There Matt made a new friend, and our guides got accustomed to our lax sense of the passage of time. Then we set out on the two-hour drive down the Indus and up a very intense canyon of a tributary, to the monastery over Lamayuru. By this point we had learned that Ladakhi gompas are required by law to be extraordarily situated, but still we were not quite prepared for the sunset that greeted us over the precariously hanging gompa and the bizarre surroundings (which is known as the Moonland). Matt then took advantage of this opportunity to get his first-day-of-trek stomach virus out of the way early. The next morning we visited Lamayuru gompa, where we sat in on the early-morning prayers of the little boy monks (Minette barely avoided being swept away by the deluge of boys when they were finally released from the prayers), and admired the collection of colorful yak-butter sculptures, as well as artifacts collected from throughout Ladakh to protect them during the Pakistani invasion of Ladakh in the 1965 war. Finally, we set out on the thrilling trek to Chilling, as you are about to discover.

Along the Indus at Alchi

Outside Alchi

Sunset over Lamayuru

Extra photos from Gompas

Back to main page

On to part V